Q & A: Recovering pose of a calibrated camera - Algebraic vs. Geometric method?

This week I received an email with a question about recovering camera pose:

Q: I have images with a known intrinsic matrix, and corresponding points in world and image coordinates. What's the best technique to resolve the extrinsic matrix? Hartley and Zisserman cover geometric and algebraic approaches. What are the tradeoffs between the geometric and algebraic approaches? Under what applications would we choose one or the other?

This topic is covered in Section 7.3 of Multiple View Geometry in Computer Vision, "Restricted camera estimation." The authors describe a method for estimating a subset of camera parameters when the others are known beforehand. One common scenario is recovering pose (position and orientation) given intrinsic parameters.

Assume you have multiple 2D image points whose corresponding 3D position is known. The authors outline two different error functions for the camera: a geometric error function which measures the distance between the 3D point's projection and the 2D observation, and an algebraic error function, which is the residual of a homogeneous least-squares problem (constructed in section 7.1). The choice of error function can be seen as a trade-off between quality and speed. First I will describe why the geometric solution is better for quality and then why the algebraic solution is faster.

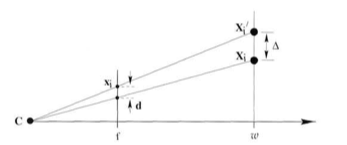

The geometric solution is generally considered the "right" solution, in the sense that the assumptions about noise are the most sensible in the majority of cases. Penalizing the squared distance between the 2D observation and the projection of the 3D point amounts to assuming noise arises from the imaging process (e.g. due to camera/lens/sensor imperfections) and is i.i.d. Gaussian distributed in the image plane. In contrast, roughly speaking, the algebraic error measures the distance between the known 3D point and the observation’s backprojection ray. This implies errors arise from noise in 3D points as opposed to the camera itself, and tends to overemphasize distant points when finding a solution. For this reason, Hartley and Zisserman call the solution with minimal geometric error the "gold standard" solution.

The geometric approach also has an advantage of letting you use different cost functions if necessary. For example, if your correspondences include outliers, they could wreak havok on your calibration under a squared-error cost function. Using the geometric approach, you could swap-in a robust cost function (e.g. the Huber function), which will minimize the influence of outliers.

The cost of doing the "right thing" is running time. Both solutions require costly iterative minimization, but the geometric solution's cost function grows linearly with the number of observations, whereas the algebraic cost function is constant (after an SVD operation in preprocessing). In Hartley and Zisserman's example, the two approaches give very similar results.

If speed isn't a concern (e.g. if calibration is performed off-line), the geometric solution is the way to go. The geometric approach may also be easier to implement -- just take an existing bundle adjustment routine like the one provided by Ceres Solver, and hold the 3D points and intrinsic parameters fixed. Also, if the number of observations is small, the algebraic approach loses its advantages, because the SVD required for preprocessing could eclipse the gains of its efficient cost function. So the geometric solution could be preferable, even in real time scenarios.

If speed is a concern and you have many observations, a two-pass approach might work well. First solve using the algebraic technique, then use it to initialize a few iterations of the geometric approach. Your mileage may vary. Finally, if you are recovering multiple poses of a moving camera, you will likely want to run bundle adjustment as a final step anyway, which jointly minimizes the geometric error of all camera poses and the 3D point locations. In this case, the algebraic solution is almost certainly a "good enough" first pass.

I hope that helps!

Posted by Kyle Simek